Introduction

For years, the Honey Bee’s anatomy has captivated the attention of beekeepers, whether driven by the joy of the craft or the pursuit of profit. This fascination stems not just from a commendable curiosity about these industrious insects but also from the essential need for such information to grasp the intricacies within a bee colony.

Effective beekeeping practices rely heavily on comprehending the behaviors and physiology of bees, both in their usual state and when facing challenges. Those beekeepers who have propelled the field forward with innovative techniques are generally the ones possessing a deeper understanding of bee activity. This understanding, in turn, is intricately linked to a thorough knowledge of the adult bee’s structure.

In this blog we will see the important anatomical features of honey bees which are important and helpful from the perspective of bee keeping and maintaining the apiaries.

General Morphology of a Honey bee

In honey bees, body parts are modified as per their food habits and social life. Like all other insects, the honeybee has three main body parts:

the head

the thorax

the abdomen

The Head

This is triangular in shape and bears eyes (a pair of compound eyes and three small simple eyes), a pair of antennae, jaws and mouth. The three small simple eyes are also called as ocelli.

(a) The Eyes

Bee has a pair of compound eyes and three small simple eyes called ocelli (which perceive degree of light). The compound eyes are composed of several thousands of simple light-sensitive cells called ommatidia that enable the bee to distinguish between light and colour and to detect directional information from the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

Bees can distinguish different colours but are red blind and can perceive ultraviolet rays. The eyes of the drone are larger by far than those of the worker or queen-bee occupying a larger proportion of the total volume of the head. These assist the drone to locate the queen as he pursues her during the mating flight.

(b) The Antennae

These are a pair of sensitive receptors whose base is situated in a small socket-like membranous area of the head wall. These serve to guide the bee outside and inside the hive as they are sensitive to touch and smell. They also assist the bee to differentiate floral and pheromone odours and to locate hive intruders.

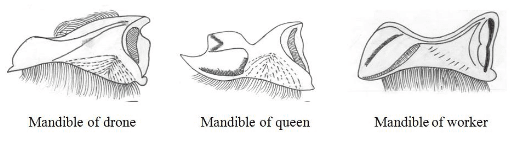

(c) Mandibles

These are a pair of jaws suspended from the head and parts of the mouth. Mandibles differ in shape in three castes (see below and compare). Workers use mandibles for grasping and scrapping pollen from anthers, feeding of pollen, to chew wood when re-designing the hive entrance, and in manipulation of wax scales during comb building.

(d) Probocsis

Unlike the proboscis of other sucking insects, that of the honeybee is not a permanent functional organ. It is temporarily improvised by assembling parts of the maxillae and the labium to produce a unique tube for drawing up liquids such as sweet juices, nectar, water and honey. The bee releases it when needed for use, then withdraws and folds it back beneath the head when it is not needed.

Thorax

This is an armour-plated mid -section of the insect. It consists of three segments: prothorax , mesothorax and metathorax, each bears a pair of legs. Mesothorax and metathorax, each bears a pair of wings.

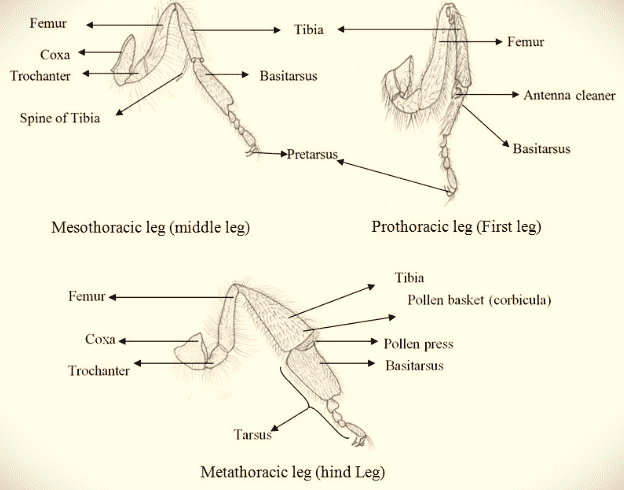

Each pair of legs differs from the other two pairs and is jointed into six segments with claws at the tip that help the bee to cling to surfaces. Legs help the bee to walk and run but various parts also serve special purposes other than locomotion e.g. sweeping pollen and other particles from the head, eyes and mouth.

(a) Legs

Prothoracic legs – Prothoracic legs serve as antenna cleaner

Antenna cleaner. This is located on the inner margin of the tibia of the forelegs. It consists of a deeply cut semi-circular notch, equipped with a comb-like row of small spines. This cleaning device is on all the workers, queen and drones.

Mesothoracic legs – On mesothoracic legs, bushy tarsi serve as brushes for cleaning of thorax. Long spine at end of middle tibia is used for loosening pellets of pollen from pollen basket of hind leg and also for cleaning wings and spiracles. Wax scales are also removed from wax pockets of abdomen by these legs. Browse our , with a variety of options to suit every taste and budget, https://www.fakewatch.is/product-category/rolex/ available to buy online.

Metathoracic legs – Hind or metathoracic legs differ from other legs in being larger in size and with broad flattened form of tibia and basitarsus.

Pollen baskets -The pollen baskets (corbiculae) are located on the tibia of the hind legs of the worker bee to enable it to carry pollen. Pollen baskets are concave in shape and are surrounded by several long hair which bind the pollen into a solid mass which is easy to carry back to the hive.

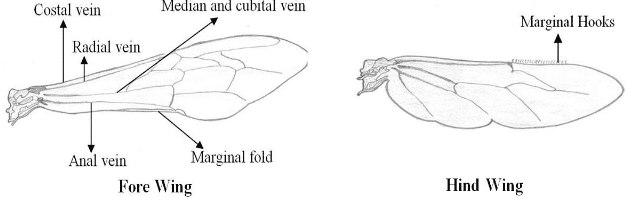

(b) Wings

Like in other insects’ wings, these are thin, flat and two layered. The front pair is much longer than the rear pair. Workers wings are for flight and ventilating the hive while those for the drone and queen are for flight only.

Abdomen

Abdomen in a honey bee is also armour-plated and contains vital parts like the heart, honey sac, stomach, intestines and the sting. An adult insect bee abdomen has nine segment while the larva has ten.

Internal Organs : The internal organs include hypopharyngeal gland, wax gland, scent or pheromone glands, the queen’s pheromone glands and the sting.

This is located in the head of the worker bee in front of the brain. It starts to mature three days after the emergence of the bee, and develops only when the insect secretes royal jelly to feed the young larvae and the queen.

(a) Hypopharyngeal Gland

This is located in the lower part of the young worker’s abdomen. It releases wax between a series of overlapping plates called sterna below the abdomen. The worker begins to secrete was 12 days after emerging. Six days later, the gland degenerates and the worker stops comb building.

(b) Wax Gland

This is located in the lower part of the young worker’s abdomen. It releases wax between a series of overlapping plates called sterna below the abdomen. The worker begins to secrete was 12 days after emerging. Six days later, the gland degenerates and the worker stops comb building.

(c) Scent Glands

A worker bee produces three main scents. The gland beneath the sting produces a special pheromone consisting mainly of Isopentyl acetate which it sprays around the spot of the sting. The odour stimulates other workers to pursue and sting the victim.

Another alarm pheromone is released by glands at the base of the mandibles. It has the same function as the first one.

The third gland is located near the rear of the abdomen. This produces a pheromone which when released by scout bees, attracts swarms of other bees to move towards them.

(d) Queen’s pheromone glands

These are located in the queen’s mandibles, and release pheromones called the queen substances. These enable her:

– To identify members of the colony;

– To inhibit ovary development in worker bees;

– To prevent workers from building queen cells;

– Help a swarm (colony) to move as a cohesive unit;

– To attract drones during mating flights.

Absence of the queen substance (for example, when the queen dies) produces opposite responses. It enables worker bees to begin developing ovaries and to build queen cells, and a swarm searching for a accommodation will not cluster, but will divide into smaller groups which cannot support the normal life of a bee colony.

(e) The Sting

A worker bee’s sting is designed to perforate the skin of the enemy and pump poison into the wound. It has about ten (10) barbs so that when it is thrust into flesh, the bee cannot pull it back again. It breaks off with the poison sac always attached to it. This enables more poison to penetrate for as long as it remains in the flesh. The sting is lodged in a special sheath and is only released when the need arises. The sting of the queen is longer than that of the worker. It is used only to fight and kill rival queens in the hive. The drone has no sting and is totally defenseless.

So, wrapping it up—learning about the anatomy of honey bees isn’t just cool science stuff. It’s like having a handbook for beekeeping success. Exploring how these little creatures are put together not only satisfies our curiosity but also gives beekeepers the keys to keeping their colonies happy and buzzing. Understanding the honey bee’s anatomy isn’t just about knowing facts; it’s about making friends with nature and keeping the bee population thriving.