Introduction

Beekeeping, in any form, is rooted in the fundamental biology of bees. Beekeepers must grasp essential aspects of bee biology to effectively manage their hives.

This knowledge encompasses the life cycle of different castes of honeybees, the structure of their nests, the division of labour among worker bees, foraging techniques, orientation, communication regarding food sources, and the reproductive process involving swarming.

By aligning hive management practices with these critical elements, beekeepers can nurture robust and healthy colonies, ultimately leading to a fruitful harvest of hive products.

In this post, we will explore the life cycle of honey bees, their social organization, and the division of labour among worker bees.

Colony Organization of Honey Bees

Honey bees are social insects and live in colonies. A normal colony, during active season is composed of 3 kinds of individuals:

- Queen

- Drone

- Worker

In an average bee colony there are:

- One fertile queen whose main activity is laying eggs.

- From 20,000 to 80,000 sterile female worker bees who do everything that needs to be done in the colony.

- From 300 to 800 fertile males called drones.

In addition to these, there are about 5,000 eggs and 25,000 – 30,000 immature bees, called the brood, that are in various stages of development. Of these, some 10,000 newly hatched ones are the larvae which have to be fed by the workers. The remainder, after the larval stage, are pupae sealed into their cells by the workers to mature- These are called the seal brood.

Life Cycle of Honeybee

The development of queen, worker, and drone castes in honey bees involves a progression through four stages

(a) egg

(b) larva

(c) pupa

(d) adult

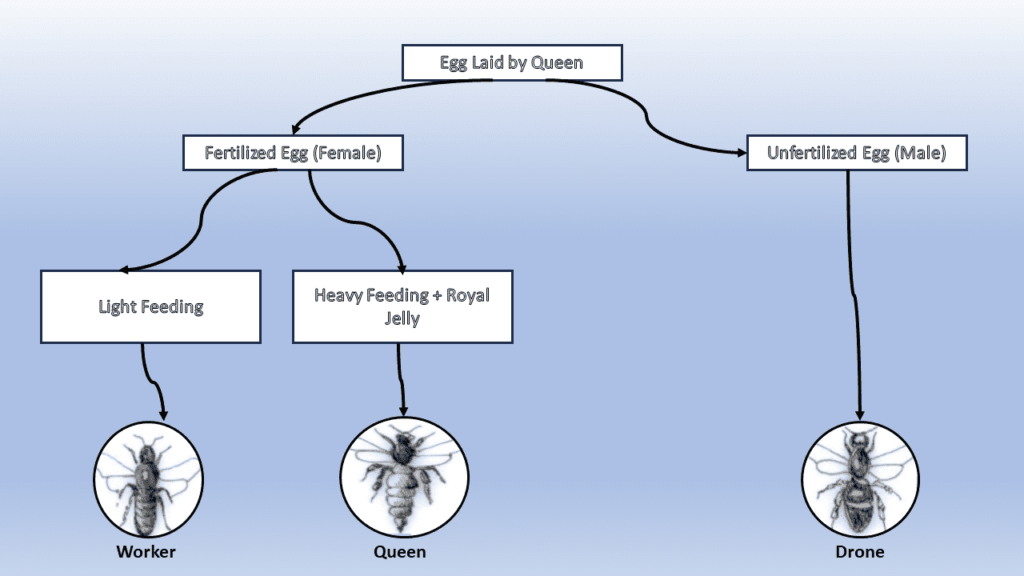

The process begins with the queen laying eggs, which are pearly white, cylindrical, and elongate-oval, measuring between 1.3 and 1.8 mm in length. Queen deposits egg at the base of cell and fastens with mucilaginous secretion. The type of bee—worker or drone—develops based on whether the eggs are fertilized or not.

After 3 days egg hatches and workers provide pearly white food in which “C” shaped larva floats. For the initial three days, royal jelly is the exclusive diet, followed by a mixture of honey and pollen. Only queen larvae receive royal jelly throughout the entire larval stage.

Cell is sealed when larva is fully grown. In the sealed cell the larvae spin cocoons and transition into pupae. Larva sheds skin five times during development. Throughout the pupal stage, the cuticle progressively darkens, and internal changes occur as muscles and organs transform into their adult forms. Subsequently, the final transformation into the adult stage takes place. The adults, using their mandibles, remove the cell capping from the inside out, unfurl their wings and antennae, and commence their activities.

The sealed cells containing worker and drone brood and honey can be differentiated on the basis of appearance.

The metamorphosis period from egg to adult is the briefest for queens, taking as little as 16 days in Apis mellifera, whereas it spans 24 days for drones. Worker bees require approximately 21 days for development from egg to adult. The precise duration can vary based on factors such as temperature, nutrition, bee species, and race.

Caste | Egg Period (days) | Larval Stage (days) | Pupal Stage (days) | Total (days) | ||||

A. Cerana | A. Mellifera | A. Cerana | A. Mellifera | A. Cerana | A. Mellifera | A. Cerana | A. Mellifera | |

Queen | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7-8 | 8 | 15-16 | 16 |

Worker | 3 | 3 | 4-5 | 5 | 11-12 | 12-13 | 18-20 | 20-21 |

Drone | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 14 | 24 | 24 |

The Honey Bee Nest

The beehive, or colony nest, is constructed with numerous vertical combs hanging parallel to each other, spaced approximately 10 mm apart.

These combs, each about 25 mm wide, consist of hexagonal cells. In the lower section of the comb, worker cells are dedicated to raising the worker brood. Around this area, pollen is strategically stored, ensuring easy access for nurturing the brood.

The upper and peripheral parts of the comb serve as storage for honey. Drones, on the other hand, are reared in specialized drone cells. Distinguishing drone brood from worker brood is possible by noting that the sealed brood cells in the former are elevated.

Occasionally, a third type of cell, known as queen cells, is constructed for the exclusive purpose of rearing queens.

Different castes of Honey Bees

Queen Bee

In a bee colony, you’ll typically find only one queen, unless there’s a situation of supersedure or swarming instinct. The queen serves as the mother of the entire colony, responsible for producing workers and drones. She stands out as the sole fully developed fertile female member, dedicated to the crucial task of egg-laying.

Unlike worker bees, she lacks the instinct or ability to nurture the brood, relying instead on a generous supply of royal jelly provided by numerous nurse bees.

Her role doesn’t extend to collecting pollen, nectar, water, or propolis, and consequently, she lacks the specialized apparatus possessed by worker bees, such as pollen baskets or wax glands. The queen doesn’t fend for herself; her sustenance comes from the nutritious royal jelly.

While equipped with a sting, she doesn’t employ it aggressively against hive intruders, saving it exclusively for combat with rival queens.

Physically, a laying queen is the longest bee in the colony, characterized by a larger thorax than a worker bee. Her abdomen becomes significantly distended during the egg-laying process.

With shorter wings that can’t fully cover her abdomen, queen honey bee can lay an impressive 1500-2000 eggs per day. These eggs include both fertilized and unfertilized ones, with worker and queen cells receiving the former, and drone cells the latter.

Upon emerging, the virgin bee queen engages in aerial mating with several drones, storing sperm in the spermatheca. These stored sperms are utilized throughout her life for fertilizing eggs.

A well-mated queen can function effectively for two or more years, although queens can live up to 5-7 years. In commercial beekeeping, queens are often replaced annually to ensure robust brood rearing.

The queen releases a substance, a pheromone known as the queen substance, which plays a pivotal role in colony organization. This substance acts as a worker attractant, inhibiting ovary development in worker bees and preventing the emergence of new queens.

The absence of the queen pheromone is detected roughly 30 minutes after the loss of the queen, prompting the colony to initiate the raising of a new queen. The pheromones in the queen substance stimulate various activities in the colony, including brood rearing, comb building, hoarding, and foraging, contributing significantly to the normal functioning of the colony.

Worker Bee

The majority of a colony is comprised of workers, making up over 98% of the population and totaling up to 80,000 individuals in a single colony.

These worker bees, developed from fertilized eggs, are infertile females. While they cannot mate, a prolonged period without a queen may prompt some workers to initiate egg laying.

Workers are equipped with organs essential for carrying out various crucial tasks that contribute to the colony’s well-being.

Duties of Worker Bees

Their duties encompass a range of activities, including hive cleaning, larval feeding, the construction of queen cells when needed, ventilation of the hive, guarding hive entrances, beeswax secretion, comb construction, nectar collection and honey conversion, pollen, water, and propolis gathering, the production of royal jelly for feeding queens and young larvae, and scouting for new nest sites during swarming.

Workers also feed drones, but if not needed, drones are expelled from the hive.

The lifespan of a worker bee is a maximum of six weeks. The initial three weeks after birth are dedicated to indoor tasks like hive cleaning, nursing the young, hive repair, royal jelly secretion, and attending to the queen, earning the title of a “house bee.” The subsequent three weeks are spent on outdoor responsibilities such as gathering nectar, pollen, water, and ripening honey, transforming the worker into a “field bee.” With no individual identity, a worker bee devotes its life to the welfare of the colony, producing approximately one-twelfth of a teaspoon of honey on average throughout its lifetime.

Duties of worker bee are related to their age

Once emerged from the cell, the worker bee start its activities. Many factors influence the regulation of division of labour between the worker bees in a colony. Glandular development according to the age of the bees and age demographics in a honey bee hive are among the important factors which determine the division between the worker bees. Duties of worker honey bees according to their age are summarized in the table given below.

Age of worker Bee | Nature of Duties Performed |

Till 3rd day of emergence | Maintain wax cells in sanitary state, cleaning their walls and floors after the emergence of young bees. |

From 4th-6th day of emergence | Feed older larvae with mixture of honey and pollen and making flights around the hive for getting layout of the hive. |

From 7th-11th day | Hypopharyngeal glands (food glands) get developed and start secreting royal jelly and feed younger larvae. |

From 12th to 18th day | The bees develop wax glands and work on building of comb, construction of cells etc., Receive the nectar, pollen, water, propolis etc., from field gatherers and deposit in the comb cells and help in keeping the brood warm. |

From 18th to 20th day | Perform guard duty |

From 20th day onwards | The worker bees take the duty of field i.e. exploring or foraging for nectar and pollen; collecting water and propolis. |

While a worker bee typically lives for only 40-50 days during the honey flow season (the active period), its lifespan can extend up to 6 months during the off-season.

In situations where a colony is without a queen for an extended period, some workers experience the development of their ovaries and become laying workers. These laying workers can lay eggs, but since these eggs are unfertilized, they only give rise to drones.

The eggs laid by laying workers follow a disorganized pattern, with multiple eggs often deposited in each cell of the comb. Unfortunately, colonies with laying workers ultimately face demise. A. mellifera capensis is an exception to this, as even from the eggs laid by laying workers, queens and workers can be raised by the bees.

Drone Bees

These male bees arise from unfertilized eggs and are nurtured with royal jelly by worker bees.

Drones, distinct in size and build from worker bees, lack the necessary adaptations for nectar collection, defense mechanisms, pollen gathering, wax secretion for comb construction, and hive-related tasks.

Instead, they consume significant amounts of food, bask in the sunshine, and have the primary role of mating with queen bees to fertilize eggs. This mating process takes place in open-air drone congregation areas, culminating in the drone’s demise.

Worker bees attend to male bees until the queen is prepared for mating, after which the drones perish. Conversely, once the mated queen returns to the hive, worker bees neglect the drones.

During periods of limited nectar, workers restrict drone feeding, gradually relocating them from broad combs to side combs, and ultimately expelling them from the hive in a half-starved state. In adverse conditions, drones find acceptance only in colonies lacking a queen or housing unmated queens.

Conclusion

In understanding the life cycles and social structure of honeybees, beekeepers gain valuable insights into the needs and behaviors of their buzzing ones. This knowledge equips beekeepers to create optimal conditions for hive health, enhance productivity, and ensure the well-being of their colonies.

By appreciating the distinct roles of worker bees, drones, and queens, beekeepers can implement informed strategies, from hive management to breeding practices, fostering a more symbiotic relationship with these industrious pollinators.

Ultimately, decoding the intricacies of honeybee life cycles proves not only scientifically enriching but also practical in supporting the efforts of those who tend to these vital contributors to our ecosystems.