Introduction

Communication is important for any social species, whether it is humans or the honey bees. Humans are believed to have the best ways of communication, but honey bees have developed some very sophisticated forms of communication that are also elegant in their simplicity.

Bees, interestingly, rely heavily on both sight and smell. During the initial phase of a bee’s life spent in the darkness of the hive, sight is irrelevant. Instead, the sense of smell guides its activities. As a forager in the open air, the bee transitions to relying on sight. Outdoors, a bee would be disoriented without its eyes, as it needs them to navigate its surroundings.

Apart from the usual five senses, honey bees have two interesting ways of communication: Chemical and Choreographic.

Honey bees can use chemical signals to tell each other about food, danger and other important things. They also have some special dances that they use to locate food sources and other communication purposes. Honey bees have a cool and complex way of talking to each other, which shows how amazing communication can be in nature.

Let’s discover the fascinating communication techniques employed by these intelligent little beings.

Bee Pheromones

What are pheromones?

Pheromones are smells that animals produce to make other animals of the same species act in a certain way. These pheromones are chemical signals that convey specific messages. They may be broadcast into the air as odors, or they may be passed between individuals through food-sharing or the touch of an antenna.

Honey bees use pheromones to keep their colony together. The different types of bees in the colony produce different pheromones at different times to make the other bees do certain things. These pheromones are like the “glue” that holds the colony together. Let us see how these pheromones help bees to communicate with each other:

Alarm Pheromone

Honey bees, being highly social insects, have evolved an intricate system of communication to address threats swiftly. The alarm pheromone is a crucial component in this defense mechanism, triggered when a bee senses danger.

When a worker bee feels threatened or attacked, it can release an alarm pheromone from its sting gland. Detecting this pheromone quickly alerts other bees that danger has been reported, and can quickly make an entire colony highly defensive.

The primary chemical constituent of the alarm pheromone is isopentyl acetate, imparting a distinctive aroma reminiscent of bananas. This olfactory cue serves as a rapid alert to other colony members, signaling an imminent threat.

Smoke as a Deceptive Shield

Beekeepers employ a strategic tool in the form of smoke to momentarily mask the alarm pheromone. By doing so, they aim to prevent widespread recognition of distress within the hive, curbing the collective defensive response of the colony.

Suppressing the immediate acknowledgment of danger helps in controlling the defensive behavior of bees, especially crucial when handling more reactive Africanized honey bees, known for their rapid and intense response to perceived threats.

The Role of Alarm Pheromone in Hive Defense

When a stranger bee tries to intrude into the hive, bees bite or sting the trespasser and release alarm pheromone, effectively tagging the unwelcome stranger as trouble. This chemical signal serves as a communal alert, aiding other hive members in recognizing and repelling a foreign bee with intentions of pilfering honey.

Guard Bee’s Sentinel Duty

Notably, guard bees stationed at hive entrances play a pivotal role in upholding security. They inspect incoming bees, using their antennae to verify if the newcomer carries the familiar scent of their queen bee, ensuring hive integrity.

If a bee is deemed suspicious, guard bees may physically repel the intruder. Moreover, the release of alarm pheromone acts as a call to arms, prompting additional bees to join the defense if the situation escalates.

Exploitation of Weak Colonies – Robbing Behaviour

In the intricate world of hive interactions, scouts from robust colonies may actively seek out weaker counterparts with vulnerable entrances.

Once a weak hive is identified, scouts return with a large number of nest mates to initiate robbing behavior—stripping the weaker hive of its honey resources.

Beekeepers call this robbing behavior, and it is commonly observed in the summer, when there are few flowers in bloom.

Guard bees must thwart these robbing attempts, preventing invaders from exploiting poorly defended hives and reporting back to their colonies about the vulnerability of the targeted hive.

Brood Pheromone

Each bee larva emits a distinct pheromone called as brood pheromone, a signature scent that undergoes gradual transformations during the larva’s development.

Brood Pheromones’ Role in Nurse Bee Behavior

The scent of brood pheromone serves as a signal for nurse bees, guiding them to the cell and conveying essential information about the larva’s dietary needs and the required quantity, depending upon whether it is destined to become a drone, a worker, or a new queen.

The brood pheromones also trigger the instinct in nurse bees to cap the larva’s cell before it undergoes pupation.

Varroa Mite: Exploiting Brood Pheromones for Reproduction

Ironically, the same advantageous pheromone can evoke a response from the honey bee’s primary adversary: the varroa mite, a parasite that exclusively reproduces on live honey bee brood.

Despite its lack of sight, the mite possesses a well-honed sense of smell, allowing it to discern a honey bee’s age through its unique odor. The mite strategically attaches itself to the younger nurse bees, responsible for caring for the eldest larvae, ensuring proximity to brood on the verge of pupation.

When a mite detects the pheromone from a larval cell that indicates it should be capped , it cunningly hides within, patiently waiting for the workers to seal the cell. This provides the mite a secure environment for reproduction without disturbance.

Additionally, the mite can differentiate between worker and drone brood, displaying a preference for drone cells due to their slightly prolonged capped phase. Despite their minuscule size, these mites wield cunning strategies that can wreak havoc on a honey bee colony.

Nasonov Pheromone and Hive Communication

Nasonov Gland

Honey bees possess a specialized gland near the tip of their abdomen known as the Nasonov gland, responsible for releasing the highly valuable Nasonov pheromone.

A common sight is bees stationed at the hive entrance, adopting a distinct posture with heads lowered, facing the hive, and extending their abdomens into the air.

The final abdominal segment is flexed, unveiling a light-colored band near the tip. While firmly grounded, they vigorously fan their wings, generating an air current that carries the Nasonov scent away from them.

Maintaining Swarm Cohesion

Primarily, the Nasonov scent serves as a signal to beckon other bees. Disturbing a hive, as in the case of hive inspection, can disorient young bees, especially those like nurse bees with limited exposure to the outside world.

The pheromone acts as a guide, allowing these bees to instinctively trace the olfactory plume back to its origin—strongest at the hive entrance. The Nasanov pheromone is not only instrumental in keeping a bee swarm cohesive during departure and temporary settlement but also facilitates unity during this resting phase.

When a new nesting site is chosen, a few scout bees emit this potent signal, effectively guiding a swarm of thousands on an extended flight. Individual foragers may emit the scent while collecting water or food, aiding other bees in locating sources lacking distinctive odors.

Use in Swarm Trap or Bait hive

The fragrance of Nasanov pheromone bears a striking resemblance to lemongrass oil. Utilizing a small amount of this essential oil can enhance the visibility and allure of a swarm trap or bait hive for capturing a new bee swarm.

Alternatively, beekeepers can opt for commercially available swarm lures containing a blend of lemongrass oil and synthetic compounds mimicking the Nasanov scent.

Honeybee Pheromone

Honey bee queen pheromone is released by queen and is referred to by many names and it is very important to the stability of the colony. It may be called “queen substance” or “queen scent” or sometimes called QMP for “queen mandibular pheromone” – although not all her pheromones are produced in the mandibular glands.

Queen substance is actually a complex mixture of numerous compounds, and the precise ratio of each is slightly different in each queen bee. This substance gives each queen a unique identifying scent, which she imparts to every member of her colony.

Let’s explore the role of Honey bee queen pheromone in the survival of colony, its effects inside as well as outside of the colony

Queen Pheromone Transmission in the Colony

In a colony, each queen has a retinue, also known as the queen’s court. This retinue is a team of young bees that surround the queen whenever she pauses in her egg laying. They feed her royal jelly and can be seen licking her abdomen and tapping her body with their antennae.

They are attracted to her by the strong pheromones she produces, and they pick up these same chemical compounds from the surface of her body, and from her mouth as she is being fed. The social honey bees share food with each other constantly within the hive, a behavior known as trophallaxis.

This activity helps to pass nutritious food, and also important information. The queen’s retinue takes up the pheromones, and in turn passes them on to other colony members.

These bees will pass them on further and further with each interaction with other bees. In this way, the queen’s pheromones are distributed throughout the hive on a continuous basis. And through this process, every bee in the hive remains aware that the queen is present and in good health.

Consequences of Queen’s Absence in the Colony

If the queen is removed from a colony, or she suddenly dies, then the level of queen pheromone in the colony will begin to drop off immediately because there is no other source to produce it.

Within a matter of hours, the worker bees will recognize this decrease, which causes a physiological change in them. They quickly become motivated to rear new queens – called emergency queens.

They will select a number of young larvae that have only been fed on royal jelly. They will begin provisioning these cells with extra royal jelly, and extend the cells outward from the surface of the comb and down, turning them into recognizable queen cells.

If the bees don’t quickly respond to their queenless situation, all the brood in the hive will become too old to successfully rear a new queen. The colony then becomes queenless.

The colony will continue to function normally for a while, but a generation of workers will begin to develop in an environment that has never been exposed to a queen pheromones.

Role of Queen Pheromones in Colony Stability

Inhibition of Worker Bee Ovary Development

Another function of the queen’s pheromones is to inhibit the development of a worker bee’s ovaries. Without this inhibition, a number of workers will begin to lay eggs. Because worker bees cannot mate, they can lay only unfertilized eggs, which always develop into drones – the male bees.

Within a few weeks, the foraging workers will be dying off from old age as the hive begins to fill up with more and more drones – the offspring of the laying workers. And because drones don’t forage, all surplus food is consumed without being replenished, and the colony population begins to collapse.

Swarming Prevention through Adequate Pheromones

A sufficient level of queen pheromone also lowers the likelihood of swarming. When a queen is given royal jelly by her workers, she actually receives some of her own pheromones, fed back to her in the diet.

If the level of pheromones she receives falls below a certain threshold, she will initiate swarming behavior by placing eggs into queen cups, which will be reared as new queens by the workers. A young, healthy, vigorous well-mated queen tends to produce the most queen pheromones.

The workers continually evaluate their queen by the level of pheromones she produces. As she ages, or perhaps if she is injured, she will tend to produce less and less pheromone, until she finally is superseded and replaced by a daughter queen.

A poorly performing queen in a small colony may produce sufficient pheromones for each bee to receive enough. But in the spring, as a colony’s population grows exponentially, each bee begins to receive a smaller share of the pheromones being spread throughout the colony, and back to the queen herself.

The result of each bee receiving a progressively smaller share of queen pheromones may trigger swarming. A young queen, however, who produces more pheromones, can sustain a larger population before the swarming instinct takes over.

Mating with Drones

In addition to their role within the hive, queen pheromones also have an effect outside of the hive. They act as a sexual attractant to male drone bees who are seeking a mate, helping to ensure successful reproduction.

Additionally, these pheromones also help regulate the number of male drone bees within the hive. When the colony is in need of more drones for mating, the queen will produce more of these pheromones, which stimulates the production of male drones.

Conversely, when the colony has enough drones, the queen will reduce the production of these pheromones, leading to a decrease in drone population.

Dance Language of Honey Bees

Father Spitzner was the first to describe bee dances in 1788, but his observations went largely unnoticed. It wasn’t until Karl von Frisch’s work in the 1920s and 1940s that bee dances were recognized as a method of communication among bees. In 1973, von Frisch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which he shared with two other animal behaviorists, for his work on honeybee communication.

Honey bees have a highly sophisticated recruitment system that allows them to maximize their foraging efficiency. The recruitment process involves scout bees or searcher bees that explore the environment in search of food sources. These scout bees can travel several kilometers away from the hive to search for flowers.

The foraging radius of a honey bee colony can vary depending on the availability of food sources and the environment. In agricultural areas, where food sources may be more limited, the foraging radius may be only a few hundred meters. In forested areas, where food sources may be more abundant, the foraging radius can be up to 2 kilometers.

There are primarily two dances that honeybee scout bees perform to communicate information about food sources to other bees in the hive. These dances are:

- Round dance

- Tail-wagging or Waggle dance, with a transitional form known as the sickle dance.

In both cases the quality and quantity of the food source determines the liveliness of the dances. If the nectar source is of excellent quality, nearly all foragers will dance enthusiastically and at length each time they return from foraging. Food sources of lower quality will produce fewer, shorter, and less vigorous dances; recruiting fewer new foragers.

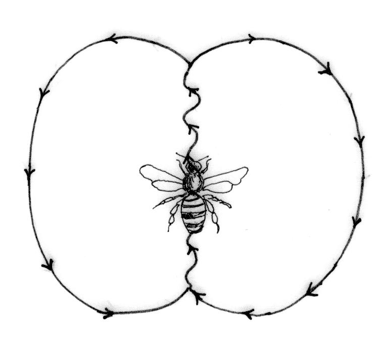

Round Dance

This type of dance is performed if food source is nearby (between 50 – 100 metres). The performing bee takes quick short steps and runs around in narrow circles on the comb; once to right and then left and then repeating for several seconds .

The dance excites the bees and they touch the performer with their antennae and then leave the hive in search of source of food.

In this dance there is no indication of direction of food and the foragers search within 100 metres in all direction using floral odour clinging to hairy body of scout bee as cue as well as from the sips of nectar which they receive from the dancing bee.

Characteristics of Round Dance

When food source is very close to the hive forager performs a round dance.

Performer bee runs around in narrow circles, suddenly reversing direction to her original course.

Repeats the dance several times at the same or another location.

After the round dance has ended, she often distributes food to the bees following her.

A round dance, communicates distance, but no direction.

Waggle Dance

The waggle dance is a remarkable example of how bees can communicate complex information to their peers without language. The dance conveys information about the distance, direction, and quality of a food source..

Communicating the Distance of Food Source

The dance consists of a figure-eight pattern in which the bee runs a semicircle, makes a sharp turn, and then runs back in a straight line to her starting point.

The duration and intensity of the waggle run is proportional to the distance of the food source from the hive. The faster and more intense the waggle, the closer the food source.

Experiment by Karl Von Frisch

An experiment was conducted by Karl Von Frisch to investigate the waggle dance’s role in communicating information about food sources.

Bees from an observation hive were trained to collect food from two different locations, one near the hive and the other further away. The bees that collected food from the closer location performed a round dance, while the bees that collected food from the further location performed a waggle dance.

Frisch then gradually moved the food source away from the hive and observed that the waggle dance became more pronounced as the distance increased.

Using a stop-watch, he measured the duration and intensity of the waggle run and found that it was proportional to the distance of the food source from the hive.

For example, a bee would run the waggle pattern 9-10 times in a quarter of a minute for a food source located 100 meters away, while they would only run it once for a food source located 10,000 meters away.

This experiment showed that the waggle dance conveys information about the distance of the food source to the other bees in the hive.

The distance is indicated by the number of straight runs per 15 seconds as given below:

Distance of food from hive (metres) | number of straight runs/15 sec. |

100 | 9-10 |

600 | 7 |

1000 | 4 |

6000 | 2 |

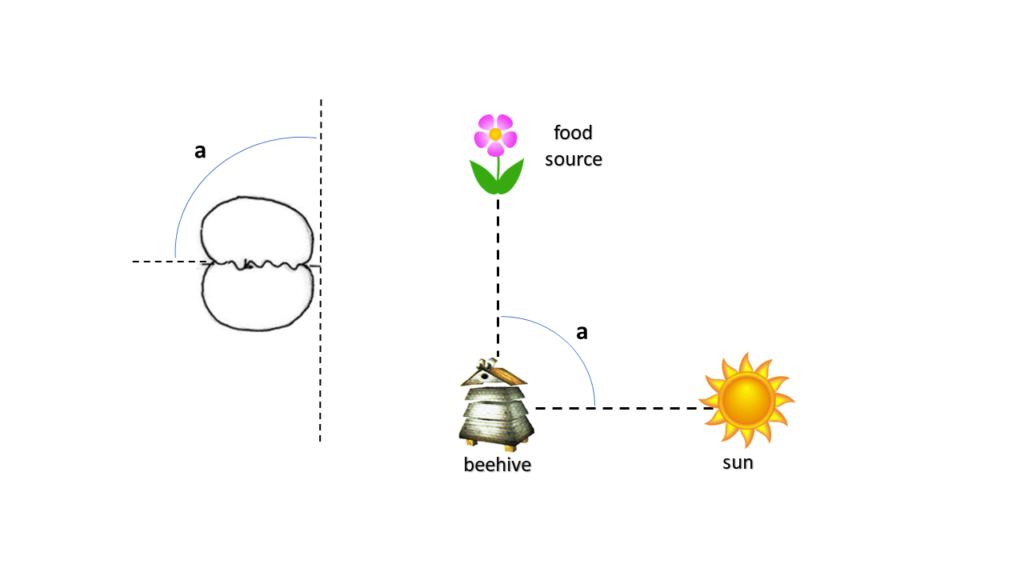

Communicating the Direction of Food Source

In addition to communicating the distance of the food source, the waggle dance also conveys the direction of the food source relative to the position of the sun. The dancer moves her body from side to side while performing the waggle run, indicating the direction of the food source in relation to the position of the sun.

In this dance the bee starts dancing on the comb making a half circle to one side and then takes a sharp turn and runs in a straight line to starting point. Thereafter takes another half circle on the opposite direction to complete one full circle.

Again the bee runs in a straight line to the starting point. In the straight run the dancing bee makes wiggling motion with her body that is why this dance is known as wag-tail dance.

Location of food is indicated by direction of straight run in relation to line of gravity. If the food is in line with the sun, bee wag-tails upwards (Figure A) and if away from the sun, it performs downwards (Figure B).

If the food source is to the left of the sun the bees dance at an angle counterclockwise to the line of gravity (Figure C) whereas, if it is to the right of the sun the bees dance to the right of the line of gravity(Figure D).

For example, if the dancer waggles to the right, this indicates that the food source is located to the right of the sun. If the dancer waggles to the left, this indicates that the food source is located to the left of the sun.

The angle of the waggle run relative to the vertical axis of the comb also indicates the angle of the food source relative to the sun. For example, if the waggle run is performed straight up, this indicates that the food source is located directly towards the sun.

If the waggle run is performed at an angle of 45 degrees to the right of the vertical axis, this indicates that the food source is located at an angle of 45 degrees to the right of the sun.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, honey bees talk to each other in fascinating ways—through dances, scents, and precise moves. This unique communication system helps them run their colonies smoothly, sharing info about food, danger, and potential new homes. Studying bee language not only teaches us about their teamwork but also gives us cool lessons on working together.

For beekeepers, understanding bee communication is like having a secret codebook. It helps them keep their bees happy and healthy. By decoding the bees’ messages, beekeepers can figure out if the hive needs more food, if there’s a threat, or if the queen is doing well.

It’s like having a direct line to the hive’s feelings, making it easier for beekeepers to take care of their buzzing buddies and ensure a sweet harvest of honey. So, whether it’s a hive or humans, communication is not just a buzz—it’s a key to a thriving community!